What is Constant in Life?

Natalie Baker: I thought that since this is the the back to school season that we could take that attitude and look at the fundamentals of what the Buddha taught 2600 years ago. This topic is a favorite of mine because I feel like it’s a topic that you can apply to your everyday, all-day experience and chew on it and see where it takes you.

How to Listen to the Buddhist Teachings

Coming into a new tradition, for those of you who are new to Buddhism, or new to the Shambhala tradition of Buddhism, it’s very helpful to start the way that we start in any school situation, which is to be a good student.

What does it mean to be a good student? If you were the teacher teaching a class? How would you want your students to come into your classroom? You can just blurt things out. We don’t even need a microphone for this one. What would you be looking for?

A: Attentive!

A: Curious.

A: Open.

A: Enthusiastic. Not with cell phones.

So with these attitudes in mind to I want you to just watch your mind as I present this material to you and I want you to notice, for example, am I open? Am I curious? When do I disagree? And pay attention to how you are as a learner.

Because I’m sure there’s going to be things I say to you this evening. You gonna go: “What? No.” Be aware of that [reaction] and if you can sort of suspend that judgment and just be like: “hmm… I wonder why the Buddha taught that.”

Enlightenment Defined

Tonight’s topic is a topic that the Buddha presented shortly after he attained realization. In the tradition of awakening, spiritual awakening in the Buddhist tradition we talked about this term enlightenment or becoming awakened. I’ll just say something about that just so it’s not just some mysterious words that we can all project onto.

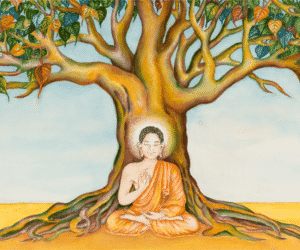

When the Buddha sat under the Bodhi tree meditating his goal was to understand the nature of existence. Why are we here? What is what is the nature of my being? Is there a way to transcend suffering?

What he discovered was… We have it a bit wrong. The nature of reality and the nature of our being is very different than how we ordinarily experience it. And so in this state of awakening he discovered both how things appear and also how they actually are. And in that state of awakening, which includes some pretty miraculous abilities such as omnipotence, being able to understand all things spontaneously, being able to know all past lives. (If you can go down that road with me.)

So this state of awakening or enlightenment wasn’t just like, ah, I feel good, but actually within it contains some very profound qualities and abilities. Transcending death is another aspect. Which for you and me are pretty hard to put our minds around, that we could actually have that kind of understanding.

But as the story goes, or as the history goes, the Buddha as he sat and came to realize the true nature of reality. When he did, he also had these abilities arise. After he attained realization, he didn’t have any confidence that he could communicate through words to his students what this realization really is.

I want to point something out to you. Nothing is permanent. You’re impermanent. The ocean is impermanent.

The Three Marks of Existence

So for a while he was silent, and he sat in meditation. But eventually he got over it and decided that he could communicate to his students in a way that would be helpful in guiding them to have the experience that he had.

And one of the first things that he presented to his students was the topic that we’re going to talk about tonight, which is what are called the three marks of existence.

So the Buddha wanted his students to know that there were a few things about their experience or the experience of being human that everybody has. And that it would be helpful for us to all be aware of what those experiences are? What those marks of existence are?

N: Anybody know what they are?

A: Awareness.

N: Well awareness is good. Yes, actually that is a mark of existence. But that’s not one of the three that he talked about. So keep going.

A: Impermanence.

N: Change things. Yes.

A: Non-self, selflessness.

N: Yep, and in the back.

A: Dissatisfaction.

N: See you guys. You guys can give my talk for me. We got all three.

1. Impermanence

So let’s take a second and just pause and just note these were the three things. Impermanence. Everything is impermanent. Everything is changing. Okay. Now I want you to think about. What in your life do you think is permanent? To see go through a whole… do the list. Like think about things that you really like that you would like to have be permanent. What’s permanent?

A: The ocean

N: So, how is the ocean either permanent or impermanent? And if you can say your name to before you speak then people can get to know you.

J: Hi, my name is Jenna. I think the ocean, I think of them as composed of waves and the waves are impermanent. So the wave motion is impermanent.

N: The waves are impermanent.

J: So the ocean…

N: So the ocean is therefore impermanent. Well, what happens to the ocean? Does it stay constant? No. Although there is this body, right? And if over the next two thousand years if it’s still here, you went down to the southern tip of Manhattan. You looked out you’d be like well the water still here. He’s shaking his head. Are they the same particles of water? No, right. Okay, let’s take your body.

Is your body permanent? No, it’s not. So that’s very interesting. Because how do we normally think about our bodies? How do we feel about aging? We’re sad right? We’re sad we resist this.

Let’s go back to what the Buddha went through. The Buddha sat under the Bodhi tree. By the way, he’d been meditating already for many, many, years all day every day. It wasn’t like he just sat down and had realization.

He worked his butt off and he had this profound experience. And then he said to his students: I want to point something out to you. Nothing is permanent. You’re impermanent. The ocean is impermanent.

Your life is constantly changing. Right? No two days are the same actually. No two emotions are the same. Right? Constantly changing. And maybe that’s not a problem. Because how we ordinarily interpret the experience of impermanence is a problem. “My aging is a problem.” “The fact that that person doesn’t love me anymore is a problem, right?” “I can’t get the bagels I love anymore. It’s a problem.”

What if Impermanence Was Workable?

What if you could notice change? Oh, the subway, yesterday came at 7 and now it’s 10 after 7 and it still hasn’t arrived. Oh, there’s change, but instead of our habitual response to that which is to get upset, to become fearful. What if we just saw it as workable. Change happens.

Maybe it’s not a problem. Maybe it’s not a problem that we die. Right? That’s a pretty shocking thing to say in this culture, right? Where you bring up death in a conversation and people think you’re being rude. But the truth is we’re all going to die.

The Buddha wanted us as practitioners, who are trying to understand better the nature of ourselves, the nature of reality, to really make note of the fact that everything is constantly changing. Pay attention to that. Don’t shy away from it? Don’t be afraid of it.

2. Dissatisfaction or Suffering

On to number two: being unsatisfied with what is. This is also called suffering; how fickle your preferences are.

We’re constantly, in every moment, doing this thing where we either like it, we don’t like it or wear a sort of neutral. Constantly. And if you think about point number 1, which is things are constantly changing. And then you notice that your mind is habitually having some sort of preference. And how painful that is.

17:46

N: Why is that painful? What’s that? Oh, yes. Thank you!

A: Because even if everything was just the way you wanted it’s going to change next moment.

N: That’s right. Even if everything is just as you want it, it’s going to change.

We have this very strong habit of constantly approaching our experience from either liking it, disliking it or being somewhat neutral. We’re never satisfied with what it is. We have no confidence, zero confidence for the most part of it, that things are just fine as they are.

So this is an interesting thing to pay attention to because usually we’re just acting it out. We’re just acting out that moment-to-moment preference. And thinking that it’s somehow meaningful. Somehow helpful to do that. Oh there I go again. I like that smell out there, but I don’t like the smell in here. Constantly judging.

3. Selflessness or Egolessness

The third constant of our existence: selflessness. This mark of existence could use a couple of hours, but I’m going to just talk about it very superficially. Then we can talk about in the discussion or if you want things to read but this is a very very very important point.

What does that mean? The mark of our existence that is always present in our experience is selflessness.

Okay, what did your mind just you? Did it go: “I have a self. I exist.” Did it object? Did it go? Thank goodness. It is a good practice to notice how your mind reacts to this idea of selflessness because for most of us, it’s slightly scary to think: “what are you saying? I don’t exist. I’m sitting here. I’m listening to you. Oh my God, if I don’t exist, what does that mean? Is it like some voidness? Should I feel embarrassed right now? Because I was thinking I exist.”

Part of the path in Buddhism is that we are balancing presenting ideas. So just in the same way Buddha had profound realization and then thought: I want my students to experience this as well so I’m going to say some things to them that I hope will help guide them to this experience, this realization.

How we practice the path in this tradition is that we take the lecture, the content, and we then start to think about it. We contemplate it.

But then we also start to find it in our own experience or not finding in our experience. But the whole point is that we work with it. We don’t just go: “Oh, that’s what I’m supposed to believe. Okay. It makes no sense to me or whatever.”

Meditation on Selflessness

The theoretical is really meant to be contemplated and also found in our meditation practice. So we’re going to talk about selflessness from the point of view of something you do experience. You have experience so far, which is your own meditation practice.

When you give yourself the instruction to go out with the outbreath. Even in this second. I want you for the next 10 seconds give yourself the instruction to go out with the outbreath.

23:38

N: Okay, what happened? And I’m not looking for a profound answer but really literally what happened? You started to tense up.

A: I became more aware of my like hyper aware like oh… Well big deal outbreath.

N: And were you always having that thought? You noticed an experience, right? Sort of like this hyper-awareness. And then you have thought. Oh, I’m kind of being intense about this. Right? But when you were first having the experience were you also having the thought?

W: No, probably not.

N: No. So I want you just to now think about that in your own experience. I want you to go back. To just that right after you gave yourself that instruction to go out with the outbreath. Can you find yourself in that tenth of a second. Right after you give yourself the instruction to go out with the outbreath. Is there a self there? What do you think? Or better yet, what did you experience?

A: I was saying it was hard to follow the instructions that wasn’t sure what the self was. It was going to be a going out with the outbreath.

N: So it’s hard to follow the instruction.

A: Yes, what’s going out? A breath is going out, but I’m not sure what else.

N: What else is going out?

A: Openness.

N: Just notice that experience. You used a word. Right? Openness. What’s the experience? Is it the word? There’s something we experience that we then call openness, right? You had an experience. And you went: Oh, that’s I think… that’s openness. I’d call that openness, right? In that experience before you gave it the label “openness.” Can you say there was a self in there?

A: No, it’s different than thinking or feeling

N: Right. So it’s like hmm… I’m not sure if in that fraction of a second, I could actually say there was a self, there in that experience.

A: I think I’m confused about two things: one is explain going out with the outbreath and also: is that a self there? I think self is a very complicated person. What do you mean by that at all?

N: What do we mean by self?

A: Or is there a self there?

N: Or is there a self there? Okay. Yes. I will. I will address what you said, but first I’d like to hear what this gentleman says and then…

A: I did feel self. I felt like this self or myself was attached or lined to thoughts and processes and as the there is an exit myself that was aligned with all of these things. It felt like it tangibly moved as well. So it did feel like the self there was a transfer…

N: Would you say that self was separate from or different from your awareness?

A: No, I think it was they were the same: self and awareness were together.

N: Huh. So, we are identifying some quality of wakefulness, awareness. That we may be called a self, right? But outside of my awareness is there something separate from my awareness that I can identify as myself? Which comes to your question of like what is it to “say go out with the out breath?”

What actually is going out with the outbreath? Is it like… Yes, let’s have… How about we call the self: awareness? All right. Well if we’re going to, you know, and that’s seems to be kind of a conclusion we’re reaching here is that when we go, “Oh, I know myself.”

Really what we’re identifying is that there’s awareness in that moment. Do we need to protect awareness? Does awareness need to lose weight? Does awareness have more value sometimes less value other times?

If we go down this road and we say self is awareness. We definitely think about ourselves in terms of liking ourselves or disliking ourselves. But if we’re going to say that really as we examine it that our self is our awareness, should we like aspects of our awareness and not like our awareness when it’s aware of other things?

A: To what you just said. Why not?

N: Why not?

A: Yeah, when is…

N: Right. Well, what then determines the value? If we’re saying, well myself is like a flowing river actually. It’s impermanent. It’s constantly changing, right? I can’t. We can do an exercise or we can we can contemplate: where is self in the body?

Because we often point to ourselves when we say “myself,” Where are you? Are you your entire body? If we remove your arms and your legs what part of you is the self? How about if we lop off your head and we have a torso and a head. Which one are we going to call the self?

This process of examination is what we do in Buddhism. We play around with things.

You should go down that river and think about: I’m thinking of self is awareness like a river where does self-esteem fit into that? Liking oneself versus disliking oneself.

A: Changes involves minutes sometimes hours and it’s totally just like a river. So just because you’re not aware of your awareness doesn’t mean that it’s… you know what I mean?

N: It’s good. It’s good. No, no, keep going. This is the process. You have to give yourself permission to try it on, right? Be like, well, what about if I think about myself like you said as more like a river?

And sometimes I like myself more. And sometimes I like myself less. But actually it’s constantly changing, right? Hmm, what would that be like? A little bit more fluid, right?

33:04

A: This is a question. But I’m trying to follow what you’re saying. I guess what I’m realizing is that in those 10 seconds there wasn’t a story or there was no personality.

I didn’t do anything unique or I didn’t do anything if that makes me… like specifically “me” in those 10 seconds. So I guess I’m realizing that you mean something around being out with the breath, being neutral or non… uncolored in some way.

N: Yes. When we go down the road of this topic of what is… how is it we arrived at the conclusion that there is a solid self, if what the Buddha is actually saying not true?

How is it that we’re making that mistake? And you are kind of coming towards through your examination of your experience what the teaching say, which is usually a narrative. Our awareness is fused with our story. And we call that story “who I am.”

The Buddha is saying that maybe that’s not so helpful. Maybe that’s not so helpful to constantly be in a narrative. In order to create some sense of: I exist.

We could know ourselves just by the sensory experience of the breath leaving the body, which as you’re noting is non-conceptual. There’s no inherent words in that experience. The label came afterwards.

Beginner’s Experience with Meditation

What is it we’re doing in meditation when we give ourselves that instruction to go out with the outbreath? The first part when we’re a new meditator is, we’re struggling with the question of what does that mean?

I’m noticing my breath. Oh, what? Actually I’m thinking. I’m talking in my head. I’m actually thinking. I’m not actually going out with the out breath.

We struggle. The first part of learning our meditation practice is struggling with the instruction. And more specifically, struggling with the difference between our immediate awareness and our commentary.

For those of you watching the US Open if is very different to turn the sound off and not hear the commentators. And then turn the sound on and there’s a bunch of the chatter.

A: I have two nephews and there’s a 5-year-old and an 8-year-old. And the five-year-old will sometimes just do what the 8-year-old is doing even though he doesn’t know what the 8-year-old is doing. I’ll go into the room because the 8-year-old is going into the room.

What is he doing? I don’t know. I’m just doing it because that’s where he is. So sometimes I feel like or not sometimes. It’s just currently. Recently felt like myself is the 5-year-old that is aligned to these bigger, more knowledgeable, more vast space.

So what happens is there’s this connection to those things that happens without even understanding why.

When the outbreath experience happened what it felt like was that there was certainly an awareness and it was mobile and my self had an opportunity to either remain in a particular space or go out with what the process or the awareness was.

And in that particular moment just now I… it was an exit because it felt as if awareness, or thought process with these particular ideas, are exiting or moving out, then myself has to go with it. So I found myself being tied to the awareness and to change.

And didn’t really… didn’t find a singular sense to myself in that particular moment.

So that was something that was interesting and that was kind of brought upon by this conversation and rethinking what the experience was.

N: Terrific. Thank you.

38:14

A: I totally appreciate that you and your awareness can be a narrative, but a narrative can be written, so you can write yourself a spectacular narrative. Are you still fueling suffering? Why because you just wrote, your awareness has just written as a great narrative. So why would there still be suffering? And how that tie-ins an impermanence? Is that because your narrative is always changing?

N: Well, is your narrative always changing?

M: Common sense is to say, yeah, over the long periods of time your narrative will change over a thousand times. But each time your awareness… you can write a new story.

N: Yeah, you can and it’s always changing. Hmm. Well, I mean with the whole question of… a mark of existence, a relative existence. (We’re not even gonna have time to talk about the difference between relative experience and absolute experience.)

What the Buddha was talking about was people’s relative conceptual experience, and he said, “Guys you’re all suffering all the time.”

“No, I’m not.”

“Okay. Check it out.”

As good students we try to remember what was presented [in the teachings.] What’s presented is that there are three marks or existence. Things are always changing. Apparently were very fickle and always have a preference. And out of that we suffer. We’re not actually content. That’s what Buddha’s saying. And the third thing being this thing we call a self, upon examination, doesn’t actually exist.

Our job is to contemplate these marks of existence and we can argue with the Buddha in our head and we can go:

No, I’m happy. We can, we should, do that. We should contemplate this and think about. Do I think this is true? Is this true in my experience? When hasn’t it been true. And why are we talking about this anyway? How is this even a benefit to me, to think about the fact that I’m going to die? Which seems like a very morbid topic. Why would that be beneficial?

And then, you come back to your meditation practice, which actually is the heart of how we come to the genuine answers, is through our own experience in our meditation practice.

Mindfulness Meditation Instruction

What are we doing in our meditation practice? We’re getting on our cushions. We’re actually feeling our bodies seated on the cushion or wherever we are. We try to have relatively uplifted posture if we can muster it. And then we give ourselves a very simple instruction.

To go out with the breath. Or you can give yourself the instruction to a stay with the entire cycle of the breath. Would you be with what is? What’s arising in the present moment? Our breath is arising that’s a reference point in the present moment.

And then we notice that we get lost in dreams of thought. Very quickly, right? Very quickly. We give ourselves an instruction less than 10 seconds. We’re gone. And then our instruction is very gently to label that “thinking.”

We’re not interested in thought in our meditation practice. Doesn’t matter what kind of thoughts you have. Which is pretty radical when you think about the fact that pretty much all day long we’re obsessed with our thoughts.

But here you just very gently label it “thinking.” No aggression, right? Just gently label it thinking. And then place your attention, your awareness on your breath.

43:23

N: What are the ways that you know the world if not through thought? There are five ways. What are they? That’s right, your senses.

We give ourselves the instruction to not be interested in thought. We’re not interested in thought when we’re meditating, but instead to notice the sensory experience because that’s all that’s happening in the present moment. Our breath is in the present moment.

And then we’re going to have an experience. And that’s it. Seems a little too simple, doesn’t it? We must be pretty awesome if that’s all we need to do. No, we don’t believe that. Not at all.

What is Buddha Nature?

I’m going to end on the foundation of all of this, which is a topic completely onto itself, which is that the whole reason this works, this meditation instruction works, is because the Buddha said that fundamentally our nature is sane.

The way that we come to experience our sane nature, our Buddha nature, our enlightened nature, is through letting go of thought. Letting go of being distracted by our thoughts and allowing ourselves to be utterly and completely in the present moment. Which means we only are experiencing the world through our five sense perceptions.

How to handle pain in meditation?

Now, sometimes our feelings are very difficult, right? And they stimulate a lot of thoughts, particularly if the feeling is pain. It’s not necessarily a smooth ride when we practice meditation because pain definitely will arise. But we don’t actually have to do anything with it. We don’t have to go into the narrative. You can be present.

The reason why we can be present is because we have this fundamentally sane nature which is what the Buddha discovered as he sat under the Bodhi tree.

So while we don’t have a self, we have a nature that’s sane. And the next thought usually is: can’t I just call that my self?

There’s a book I recommend if you want to carry on this journey of understanding self and selflessness. Is a book of compiled lectures that Trungpa Rinpoche gave who is the founder of the Shambhala centers. It’s called The Sanity We Are Born With.

It’s a series of lectures he gave to people in the mental health field. And he talks about the self and about the basic, sane nature, also called basic goodness. All sorts of nice juicy topics.

Well, I do hope that you practice regularly. Do your meditation practice. Explore your mind. 10 minutes a day. See, what arises. Thank you all for coming!

Summary

When the Buddha sat under the Bodhi tree through his meditation practice he came to understand both the nature of reality as it is, and also how it appears. This experience is called ‘enlightenment’ or Buddhahood.

When he first started to teach after his realization he taught about the latter category, relative truth, as having three marks to our existence. These three marks are: impermanence, suffering, and selflessness.

Things, though we think they are often permanent, are not. The only thing constant in life is actually change. Because we have a hard time accepting impermanence and clinging to things as permanent, we suffer and struggle.

But because things are impermanent so is the self, and if we can experience our egolessness or selflessness through our meditation practice, we come closer to the true nature of reality.

In Buddhism these ideas are not taken as true until we have found them directly in our own experience. Through our mindfulness and awareness meditation practices we can come to know these three qualities directly.

Liked the lecture? Get your free copy now.

Did you like this piece of content?

Say hello to our team!