Parable From the Time of the Buddha on Grief

There’s a story from the time of the Buddha of this young mother who was very thrilled to give birth to her first son and cherished him dearly. But unfortunately, he died shortly after childbirth. And she was devastated. And she had him wrapped around her not wanting to let go of his dead body. And running from person to person in her village asking if there was anybody who could bring her child back to life and help her.

And someone in her village said, “Go and see this spiritual teacher named the Buddha. Maybe he can help you.”

So, she went and had an audience with the Buddha and asked him if he could please help her that she couldn’t live without her newborn son. And the Buddha responded and said: “Yes, I can help you.”

And she was overjoyed. And the Buddha said, “What I need you to do though, is go and find me a mustard seed. And she was immediately very excited because mustard seeds were common in every kitchen and so not a hard task to accomplish.

But before she set out, he said to her: “But there’s one other part to the instruction, which is that you need to find a mustard seed from a family that has not experienced death.”

And so, she set out going household to household. And the first home did indeed have mustard seeds. But then she asked has your family experienced loss? And they described an uncle dying the previous year. So, she had to move on to the next household. And the next household it was a grandfather. And then it was a stillborn child. And she kept going. And upon each home and each conversation that she had she had an experience of recognizing that everyone experiences loss. And although she assumed that she couldn’t survive her loss, she experienced in these people she met, that they, too, had suffered the same pain and were still here and still carrying on.

And so eventually she went back to the Buddha and said to him: “I understand that there’s no such thing as life without loss.”

And at that point she decided to practice meditation and follow the Buddha’s teachings.

I tell you this story in part because we have been struggling with the pain and confusion of what does it mean to experience loss? How do we work with that? Since the time of the Buddha: 2600 years. This is part of what we’re looking at when we practice our spiritual path.

So, if you [the audience members] don’t mind sharing, I thought we could just… and you can just shout out. We don’t have to wait for a microphone. I’ll certainly repeat them in the microphone. But if you want to share what for you is loss.

Like when you think about this topic tonight. Making friends with loss. What comes up for you?

[audience member] I’ll start. I was thinking about the fact that for me recently. I feel a lot of pain from the loss of time. What I feel is not having enough time.

I love people to talk to each other because I feel like a lot of the lessons come from learning from each other.

Yes, life changes. The loss of your childhood. Death of a partner. Loss of friends. Big and small. Mother sinking into dementia. Longing to see someone again. Thank you! Lack of control. Loss of Support. Loss of Health. Losing someone to addiction. Loss of being sure. The loss of what might have been. Yes, that’s a juicy one. Absolutely.

So, for those of you who don’t… haven’t been to one of my talks, I love people to talk to each other because I feel like a lot of the lessons come from learning from each other. So, I would love for you to turn to a neighbor and introduce yourself. And to just talk for a little minute or two each. What makes loss difficult for you? What is the part that is a challenge or parts of loss that are a challenge? And you can just spend a couple of minutes just talking and listening to each other and then we’ll come back together as a group.

So I’m going to invite you to share something you learn from your conversation about what makes it challenging to experience and work with loss and you can just raise your hand, but we are going to wait for the microphone so that everybody can hear you. You guys just resolved it all? This is gentlemen here.

What Does Grief Feel Like?

M: Hello! The two of us did resolve. No, I’m just kidding. But we were talking about just being able to sit with it. Difficulty of you know playing simple sitting with it.

N: With it. What’s it?

M: The feeling of loss whether it be mental or physical or both? I think it’s a package usually.

N: And what does it feel like?

N: For me personally?

N: Or you could just… theoretically.

M: I think the human body stores it in certain places, whether it be the shoulders or like a physical reaction. And then the mental reactions are probably endless the mind will chatter until you cease to exist.

N: It’s a lot of mental chatter and tightness in the body.

M: Yeah, I think it can even manifest as illness. Even just a meandering mind or an absent minds. Hard to pay attention, you know. Things like that. And loss can come in all sorts of things. So, depending on much of a punch it is, you know, it could take a very long time to get through the physical and the mental aspects of that. At least that’s what I think.

N: Great. Thank you. Yes, in the in the back there.

W: I am a believer in Western psychology. I think that if there’s big loss in your formative years that didn’t get a chance to heal then the little losses of the present can evoke that. And so, they get tangled up and instead of being a smaller loss it can become this huge piece. This huge loss. And when I can separate that… Like always protecting against loss because loss means this really devastating. Peace.

N: Great. Thank you. So, the losses of our past can pop up when we’re experiencing the losses of the present. And then we can find ourselves protecting ourselves from what feels like devastation. Mmmmhmmmm. Thank you. Was there somebody over here?

M: Thank you. What really seems to trouble me is that we don’t take a strengths-based approach to loss recognizing, for example, what Thich Nhat Hanh will say: long live impermanence. We always perceive loss of good things over not good things. So, we have this duality and that we kind of almost feel that that good means loss of goodness. With a denial of both the impermanence but also that sense of emptiness. So, we’re separating this from ourselves and we kind of feel as though and I think that’s debilitating. I’m not trying to be Pollyanna about it. But I just think that there’s some tools that we can use in Buddhism to try to reconcile that loss with a strengths-based approach.

N: Thank you. Yeah. So not recognizing…. that the gentleman here and then over here. Not recognizing that loss. And impermanence also means the loss of the things that we don’t like but we always focus on the loss of the things that we want to keep permanent.

M: I was thinking of the story you gave us from the Buddha. And the element of empathy that could heal in some way, you know, knowing that and getting to know other people who actually have experienced this or similar loss. Not simply the intellectual knowledge of the… Okay, everybody has lost someone you know, but actually talking to them and being with them, which gets us out of our, you know, shell. And has some kind of healing effect, you know, it’s not the resolution per se, you know. Because their loss is still there, but it’s seen in a different light. In a new context. So, this lady Meghan, [discussion partner] … So, we ended up starting sharing something very different and not going to be specific. But then they talking and they liberating we found some kind of common experience. And you know, that’s something…

N: So, what belief gets shattered when we have the experience of a shared experience?

M: Not to be unkind to myself but this is self-preoccupation, right? Not that this is intentional, but when the certain problem overpowers us, we forget that there’s sometimes even bigger suffering. Since we’re talking about the Buddha teachings this kind of natural ability… We have that, Shambhala will call, basic goodness, or our Buddha nature whatever that’s naturally compassionate naturally willing to be empathetic if we only give ourselves the chance to be that.

N: Yes, we forget that part. Yeah. Well said. Thank you! And then there’s this gentleman here.

16:34

M: Thank you. I guess a lot of the things that were said mentioned us wanting to hold on to whatever situation. And you know, that’s something big for me. It shows earlier today I was talking to a co-worker of mine who hates his job and he has hated it for the last year or so. Yet, he’s terrified of losing it at the same time. And what we were digging in and we’re like, well, what are you so afraid of because it’s been a year that you felt this way. So, he’s told me like he has two years’ worth of savings. So, like the downside of losing the job and he’s in technology seems like probably find something else eventually are minimal. But the fear, the real fear that he has regardless, even if it’s a bad situation of the unknown messes so hard for him. For me, I think I empathize a lot when I when I hear that to kind of deal with that change. So sometimes it’s not just fear of something positive going away. It’s just whatever we have. We just tend to hold on to it.

N: Yeah. Yeah, and when we start to contemplate letting go of it, right, we start to notice there’s all this fear there, right? And fear we perceive as an indication to just stop. Stop. Thank you.

M: So, I was thinking that we tend to define ourselves by things that we have. And loss helps us because when we lose something, we realized that that we’re still here and we’re not that thing that we used believe was us. It helps us rediscover ourselves.

N: And what do we have to tolerate? What do you when you think about the process of experiencing the loss? And then what’s the process from that moment until it registers that there’s actually, as you said, there’s a gift? Also, what do you have to tolerate as you go through that process?

M: I think it’s all of these beliefs that we had. We used to lead our life with these beliefs and then when there is shattered then it’s realizing that maybe we’re not living life as we really should have.

Two Parts to Loss and Grief: Emotions and Beliefs

N: Yes. Thank you. Yeah, so one of the things that’s coming out of what you’re talking about is that there’s really two aspects of what we’re experiencing when we go through the process of loss.

One side of it is the emotional part of it the actual pain and sadness, and fear. And then the other side of it is that our ideas of how we thought things were or how we thought things should be they dissolve or get shattered. And so these are the two parts that we want to examine loss from the point of view of our beliefs about how we think things are. How we think they should be. And loss in terms of working with our emotions that arise when we experience loss.

The Buddha’s Teaching on Loss: The First Noble Truth

The first aspect of life that the Buddha wanted to communicate to students once he attained Buddhahood… so we could say a complete understanding of absolute truth. Complete manifestation of wisdom. How things actually are. Which we call Enlightenment or Awakening. But one of the first things that he wanted to point out was the fact that we experience loss and suffering as being human that actually that is how things are in a relative way.

Let’s first acknowledge that truth of suffering and then we can start peeling back the next layer of that which includes a belief in permanence of things. We acknowledge that certain things we really want to keep around. And on some level, we are shocked when those pleasant things change. The unpleasant things we are perfectly happy to acknowledge and have their impermanent nature reveal itself.

We have this idea that things should be as we want them and that things are actually solid. Part of the Buddha’s first teaching about the truth of suffering was actually that things are not solid. Things are not permanent. Things are compounded and always changing.

How to Make Loss Less Painful

On the Buddhist spiritual path the first act is to look at an idea: you don’t actually have to be confused because you’re experiencing a sense of loss and a feeling of pain and suffering because of your losses. Which if we just contemplated that, right? If we expected when we wake up in the morning anything could happen, right? I could go to my job at the building could be there. Or I could go to my job in the building could be gone. That’s in the realm of what it means to be a human in the world. I could fall in love and love this person and the next day they tell me: I’m not that into you. And that we could hold that as “Yep, that’s what happens.”

But what we do is that we want to grasp, right? We want to solidify things. And then when things manifest their nature, which is to constantly change. We get all freaked out. We get scared. And this is the Buddha’s description of how we suffer. We’re actually basically confused about the fundamentals of existence.

We wonder why we can’t create our harmonious political situation. We can’t even acknowledge the basic reality which is things are constantly changing all the time. Every day we wake up. We look in the mirror. We’re looking at a different person. We are constantly changing but we ignore that. We ignore that because as someone else pointed to that when we experience loss, we realized we’re not in control. And then we experience fear.

How To Work With Emotions of Grief

And now we’re going to move on to the second part, which is the emotional part. There’s a thought which is: I don’t like fear. We have a preference. And so we do that defensive dance that somebody mentioned earlier.

Fear

We think we’re going to be devastated [by the loss] so we try to protect ourselves from that fear. How does that go?

Then we add another layer of confusion by trying to distract or change our environment because that fear is telling us to do something because we are in danger. To bring in the western psychological understanding here: fear is the brain’s response to perceiving something as a danger.

And then we get angry. And now we’re fighting. We are either fighting with ourselves were fighting with the world. Why? Because we had a glimpse of reality which is, we’re not in control and things are changing and there’s basic pain. Then fear, it automatically arises and and that scares us, and we act it out.

What Is The Nature of Emotions

The Buddha understood in detail how we create suffering and his teachings were laid out to help us understand how we needlessly create pain and confusion. And how we are still workable despite it.

Because we’re not actually relating with our experience and the Buddha taught that we can afford to relate with our feelings.

Emotions are not solid. They’re often not accurate. They are energy. They don’t actually define who we are. And if you really contemplate it, right, an emotion really is an experience. And then we label it anger, sadness.

The Shambhala Lineage

In the Shambhala tradition, which is a Buddhist lineage that is meant for secular folk like us who have day jobs and lives. These are teachings meant to be integrated into our daily life. We don’t have to run off to monasteries and nunneries to work on ourselves spiritually. The Shambhala approach is coined in the language of warriorship. But warriorship not in the sense of going to war against an enemy, but from the point of view of actually being able to transcend the need to be at war. The need to be aggressive in order to manifest and be in the world. The language of Shambhala is very fruitional.

Mindfulness of Loss and Grief

The point of view that’s taken here is that we can afford to meet our experience directly. What makes this whole mess that we call “me” challenging is that we have this belief that when we’re experiencing the pain of loss, the fear of loss, we think that we don’t have what we need and that the experience we are having we can’t tolerate. We can’t be with. We believe that thought.

There’s the feeling which is a very yucky feeling. And then there’s a belief that goes with that feeling, which is I can’t tolerate this experience. I can’t tolerate this reality. And we just automatically believe that thought.

But the teachings actually say that we can tolerate our experience. And that thought we are having we can’t be with the pain of loss. And so we get even more scared. And we do all sorts of other things right to try to avoid our experience.

I will read you a line from a Shambhala root text that is in Shambhala: Sacred Path of the Warrior, which is a book that Trungpa Rinpoche wrote. The book is a compilation of talks he gave in the late 1970s and early 80s on the Shambhala teachings. But this is a line from the root text is what is called “terma.”

In Buddhism, there is an idea we could say or reality if you believe it, that wisdom arises. This is wisdom that’s not born out of confusion, but it actually is genuinely in accordance with how things actually are. The wisdom teachings are what we contemplate to contrast against what we think so we can chew on these things and notice what’s different and what’s being presented in the wisdom teachings versus how we ordinarily think of things.

This line from the Shambhala terma says:

That mind of fearfulness should be put in the cradle of loving kindness. And suckled with the profound and brilliant milk of eternal doubtlessness.

That’s a pretty fruitional statement. Eternal doubtlessness. When have you had a moment of eternal doubtlessness? Right. [Never?]

The Shambhala teachings are saying this is actually who you are. There is the problem presented, which is our fearfulness. When we experience loss, we’re also right along with that we’re experiencing our fear.

Steps For Working With Grief

First we just acknowledge. Yep. That’s what happens. We get really scared all the time. Super fearful.

But then what do we do? Put it in the cradle of loving kindness. And suckled with the profound and brilliant milk of eternal doubtless. That would be nice, right? Of course, we don’t believe it at all. And hence we have a path.

Meditation for Grief

If you want to just take good posture, good head and shoulders. I’m going to guide you through a meditation practice because you always put the two together: Buddhist teachings and meditation practice. These two we always bring together so that the teachings start to come alive in your own experience. That’s the whole point.

First of all, I think it’s good to start by just acknowledging that we kind of like to give ourselves a hard time by thinking that we’re alone in our pain. And so it’s good to first start by remembering the story of Kisa Gotami that’s the name of the woman who lost her son. So we can first start by acknowledging: “You know, I’m not alone in this struggle. We all we all worry about our losses. And we all feel pain of our losses.”

Then we find our breath and allow our attention to be on the breath. Awareness of the movement of our chest as we breath. Any thoughts that distract us during our mindfulness of breath we simply label “thinking” and redirect our attention back to our breath.

Once we are stable in following the breath then we can now turn our attention to our loss, our grief. You may recall a face or the felt experience of sadness. Please keep this part simple, just allow yourself to notice, and have that bare attention of the experience. If you start to have a lot of thoughts about your loss, then come back to the breath, and find the loss as a felt experience.

In this practice we are becoming familiar with the immediate experience of our grief and allowing ourselves to have the confidence that we can be present to it, in a very gentle, simple and immediate way. And in doing so, we start to make friends with the loss and find our fearlessness.

So we could have a short discussion if people have comments or want to share their experience doing this practice.

35:52

M: One of the things that came up when I was discussing with my discussion partner was the time period after a loss. After the ground from beneath you gets wiped out from under you and I’ve always remember this quote and I have no idea who it’s from. But it sticks with me and it’s the idea that during the times when we don’t experience loss, we stack all these teachings of wisdom on top of our heart and the hopes that when it breaks some of it might seep in through the cracks. I don’t know who said it, but it I love it. And I think it’s a great metaphor for that time period after a loss when you… Everything is so raw that you experience the entire pantheon of human emotions in a way that you don’t. And in that way maybe that can be part of the other side of the coin of loss and part of the gift that comes after a loss. That’s a thought I had.

N: Thank you. Yeah, I can see it. Seeping. In Buddhism there is another similar expression speaking to what you mentioned is that death is a time of great blessings. For the reasons, you just described, that breaks our hearts and now we’re so much more raw and exposed and we can meet the world and be sensitive to the world in a way that we can’t when we’re busy living our lives and things are kind of going our way and we’re just going along.

M: Could you talk please a little more about what it means to… What’s to put your pain in a cradle of loving kindness? We see that term make friends with your unpleasant thoughts and I’ve asked people what does that mean? And everyone goes silent? So what is one doing when one is cradling one’s pain in loving kindness?

N: Do you have children?

M: Yes.

N: Okay. You can answer that question.

M: Are you cradling yourself, which doesn’t exist.

N: Don’t be… don’t be… I’m pointing you towards your children to make it more experiential. Don’t make it intellectual. Like really like have confidence that you know what this instruction is and describe it.

M: Comforting.

N: Because what is the view you hold as a parent when you comfort your child? They are sad. Their friend doesn’t want to play with them. Or you know something they love broke. And you comforting them and what is the view that you’re holding as you comfort them? You’re not speaking, but it’s just there.

M: You’re okay.

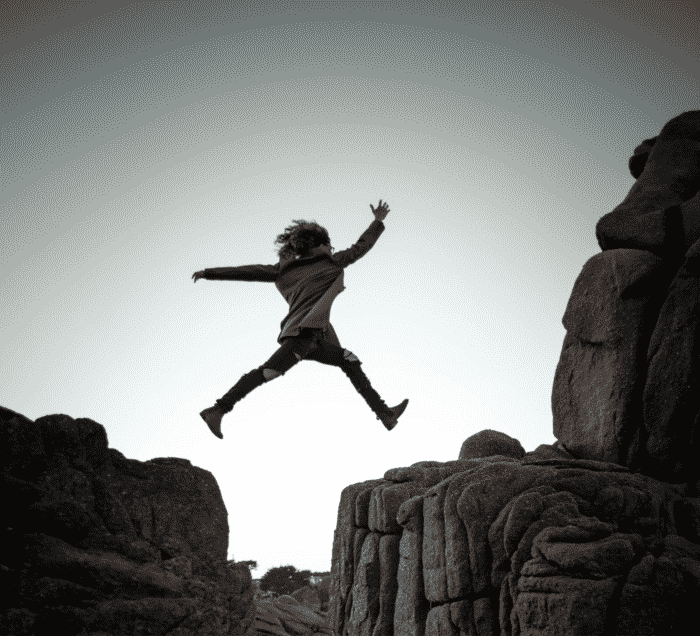

N: Yeah, you got it. So going back to your dilemma with your children, you know, really trust yourself and hold the view that it’s okay. Trungpa Rinpoche used to say all the time: take a leap. Take a leap. That’s what that’s what you’re doing right now. I don’t know. What’s the answer? Yes.

The Practice of Embracing Impermanence

M: I’m trying to think back over your talk about what methods we might use to work with loss. And what you’ve brought up impermanence and I’m I didn’t really hear you say it but I’m guessing that the acceptance and understanding that life is full of impermanence will help dissolve and make less the suffering of loss. Is that correct?

N: Yes, but you should test that one. That’s what we do: test. The Buddhist teachings will present an idea which is to be tested …actually. The Buddha said a mark of our existence is that things are constantly changing. They’re not permanent. They are impermanent. And so we should have that in our expectation. So, then you can do this as an experiment. Tomorrow. Wake up and say:

Okay, today I’m going to really accept and embrace that things are going to constantly change. They’re going to constantly be different than how they were yesterday. How I want them to be. And I’m just going to notice what that’s like to be with the fact that things are impermanent. Including my own state. This thing I call “me.” And also, be curious about: how do I change? My moods. My thoughts. All of that.

Bringing Loss Into Our Meditation

M: One of the obstacles that I noticed you talking about is our wanting things to be different than they are. Not being in the moment accepting what is… And it occurred to me even though I didn’t hear you go into it that one way we do that without judgment is meditating. So, we could actually bring loss into meditation in a non-judgmental way and that would be so different than our everyday way of fighting at or whatever.

N: Yes. It’s great to bring our loss to the [meditation] cushion because the whole objective of practice is to come back to what is. So if you are experiencing a lot of pain from something whatever it is, you know, that you could also notice that during your meditation practice. And instead of bringing your attention to the breath you could bring your attention to that feeling and just be with it. Don’t try to change it. Don’t analyze it. Just be with it as a sensation. That’s the object I’m with it. And then to be curious about well, what’s that? Like, what do I notice?

M: Thank you very much for your talk.

N: Well, thank you for filling in the gaps. So maybe we should stop here because it’s 20 to nine. And I want you all to be able to enjoy the refreshments before we part ways and certainly we can keep the conversation going. Do we have any… final? No. We have no final. So, thank you all for coming and please enjoy the refreshments.

Summary

From a Buddhist point of view grief is a part of life, and it is a workable part of life. To deny that loss and the pain of loss is part of living, is to add to our suffering. The first step in making friends with loss is to accept that it is part of our experience and not demonize it. We can do this in our attitude and also in our meditation practice. When we touch our pain as it arises in our immediate experience it becomes less painful. When we remember that we are not alone in our pain, but that it is a shared human experience, it becomes more workable.

Liked the lecture? Get your free copy now.

Did you like this piece of content?

Say hello to our team!